Continuing from Larry Shaeffer’s Legacy Part 1: In The Beginning, There Was Music.

Some make history, while others preserve it. It is rare to find an individual that does both. It takes one who marries the past to the future and forms a union that introduces ignorance to wisdom, wrong to right, arrogance to humility, and fear to hope to truly understand that everyone can own a part of history if only willing to make their own while saving the history of others. Larry Shaeffer is such a man.

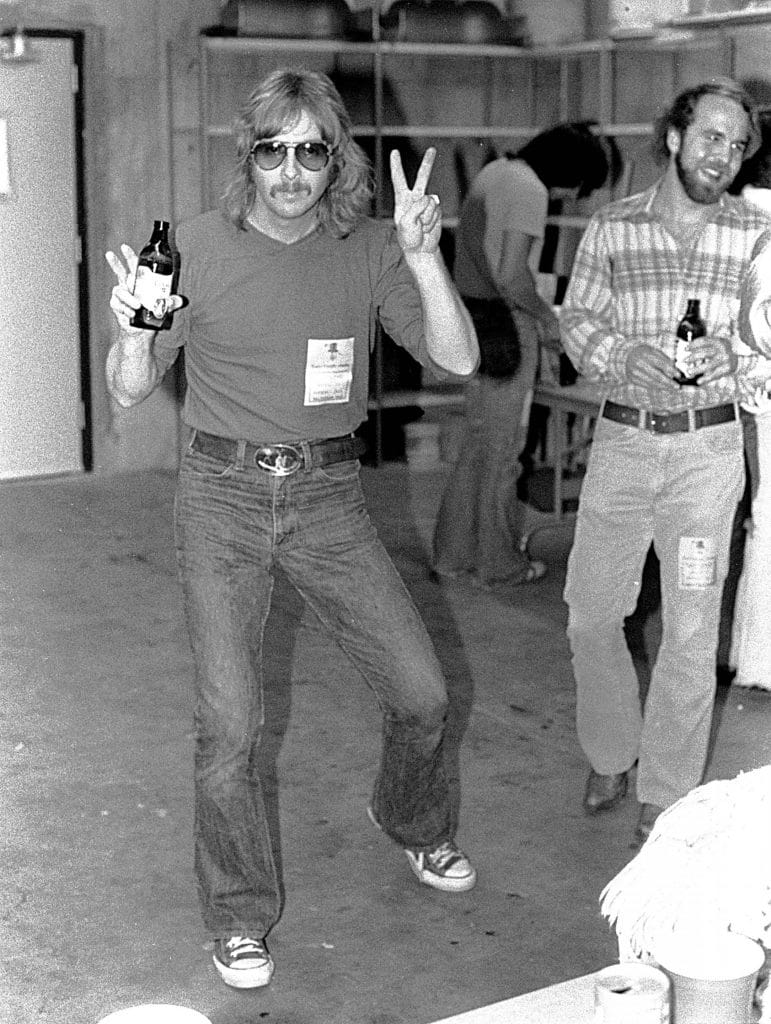

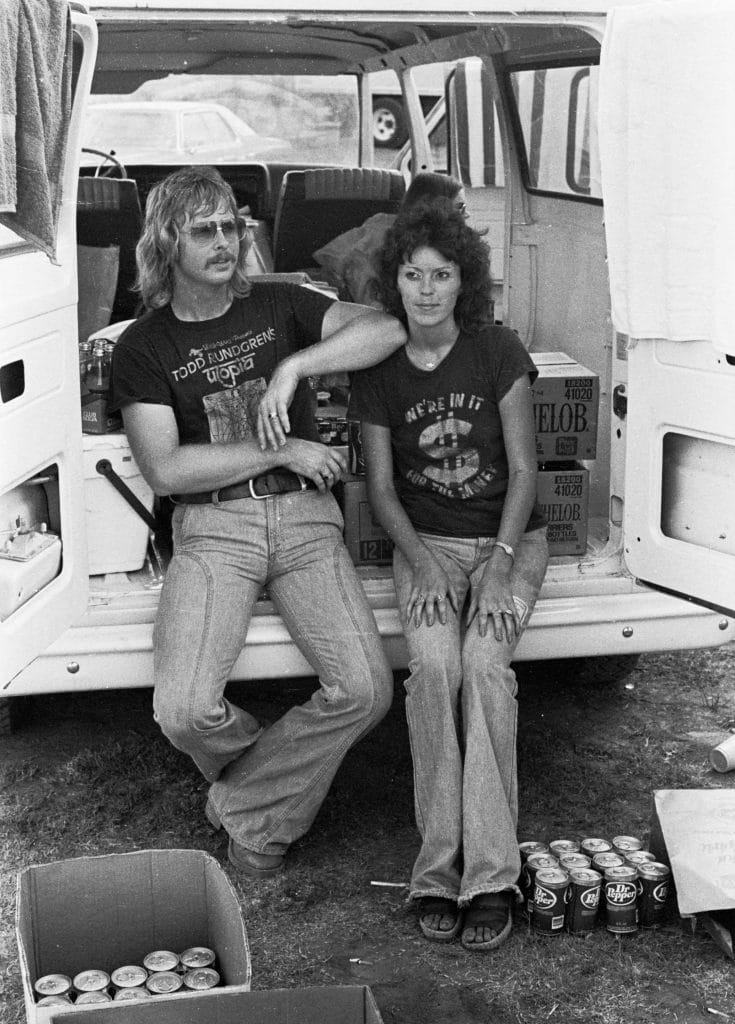

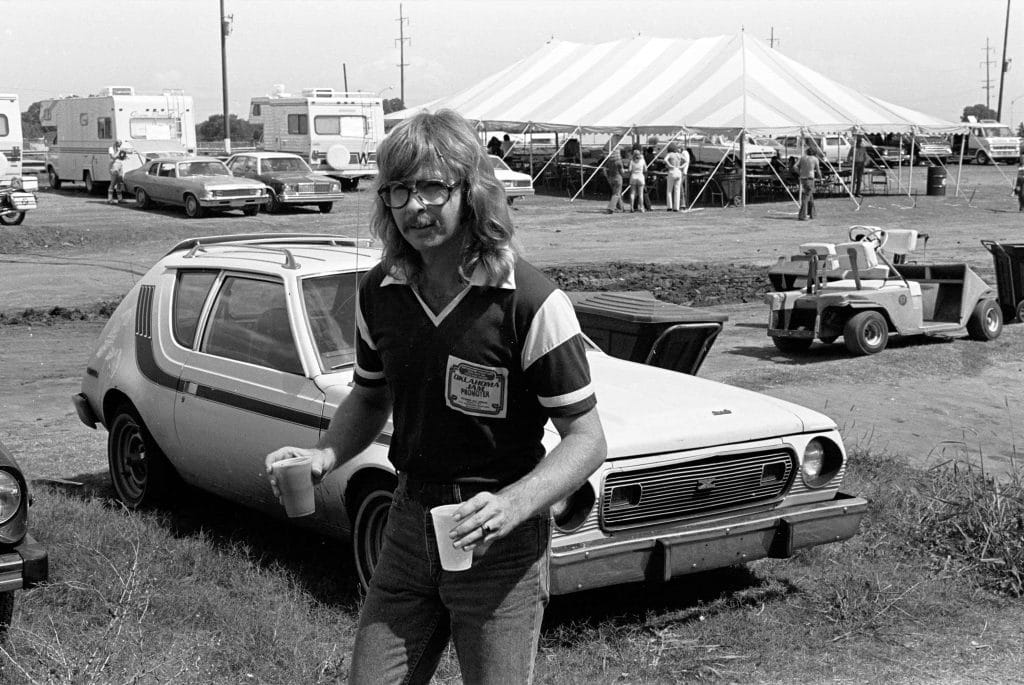

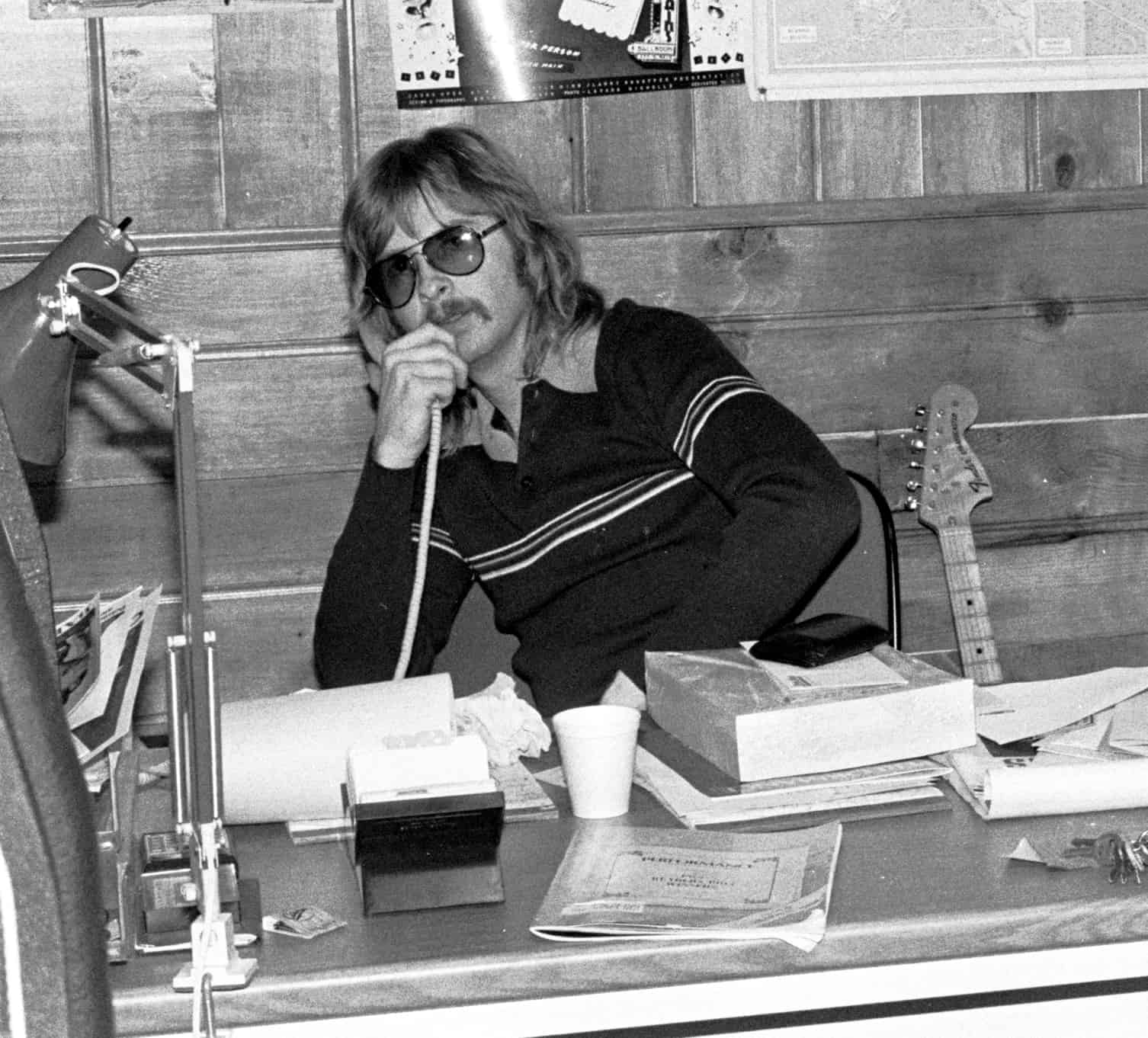

The skinny kid from the Lake Keystone area now had a band to promote with Black Oak, Arkansas. Larry was about to make his debut performance leading into the music business with his then partner David Miller and their company Little Wing Productions, a name from the Jimi Hendrix song of the same name. He knew that he had a lot riding on this. In those days, Black Oak wasn’t a sold-out show band, so he had to become creative to sell enough tickets to make the show successful.

Although he had his first show on the books, he had no idea what to expect or how to sell a show.

“There was no road map or set of instructions on how to do this,” Larry said. Parking cars for a living making $44 per week with the occasional quarter as a tip, Larry had a lot of hopes on this first show if he was ever going to go from parking cars to driving ones, others would park. Always being one who can spot an opportunity, he took advantage of the state fair in Tulsa and was on the lookout for any hippie that reeked of weed and/or rock n’ roll.

Using $3,000 borrowed from his local bank, which he secured as collateral with his 1965 Volkswagen and 1950 Harley-Davidson motorcycle, he bought a radio ad from a Tulsa station, rented out the Tulsa Municipal Theatre (Now the Brady Theatre), and printed out mini-posters which he handed out at the fair to those hippies for its duration of ten days. It turns out that his efforts paid off. T e show sold out. ( or a fun anecdote about the day of the show, tune into the podcast with Larry, which will be released soon.)

It’s Raining Money!

By his admission, Larry says he was not astute enough to know if he would make any money from the show. But the was finally in the music business… and a concert promoter, no less.

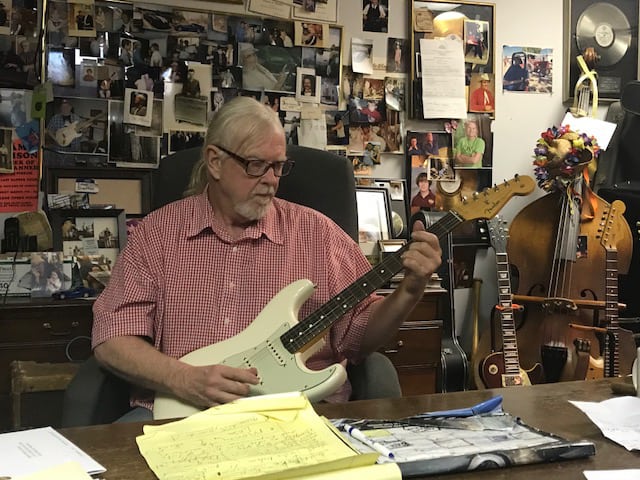

“I made enough money that evening to pay the band and the bank and still put $4,000 in my pocket! I had a bag of cash at settlement. One of my favorite memories is getting back to my apartment in downtown Tulsa after the show, opening that bag of cash, and slinging it on the bathroom floor, living room floor, on the couch, in the kitchen, on the TV, and everywhere else. I looked like it was raining money,” Larry remembered as he grinned across his desk.

This was his first redemption, as he called it, that he was on the right track. Little did he know back then that all shows weren’t that successful. However, his tenacity and boldness would once again strike gold before he would eventually conceive the thought that gold mines have shafts. H s next move would certainly be bold and show how committed he was to his endeavor.

“I was pumped! S the next day, after picking up the money, I had it in the back of my head that Merle Haggard was going to be a big star. I don’t know why but that was the name I came up with,” Larry said. After some quick research, he learned that Haggard had played Tulsa the year before when he had been drunk and “played a half-ass show.” However, he still believed that Haggard would be a hit.

He began calling Haggard’s office in Bakersfield, California, hoping to talk with his manager Tex Whitson. A had been his luck for most of the previous year; no one called back. T e receptionist would take his messages, but the phone on his end wasn’t ringing. H needed an in, and it soon came when finally a different receptionist answered the phone. As impossible as it may seem today, She nonchalantly told Larry that Haggard was in Nashville at the annual DJ Convention. She then said to him that Haggard and Whitson were staying at the King of the Road Hotel. That was all that he needed to hear.

Flying High On Stand-By

“My father worked for American Airlines back then, so the family could fly standby for free. The very next day, I am flying to Nashville. As soon as I land, I take a cab to the King of the Road Hotel, walk in and ask what room Haggard was in.” And without hesitation, the desk clerk gave him the room number. (Oh, the times of innocence… how they have faded.) That knock on the door of the King of the Road Hotel would open the opportunity he dreamed of.

“I knock on the door, and a man named Fuzzy Owen answers. These guys stay up late, and it’s obvious that they are just waking up. I see Merle through the doorway rubbing his eyes. I looked like this anemic blond guy who was too young to talk to them.” (So he thought that’s what they thought.) “Fuzzy was very gracious as I told him why I had come there. He then told me to go down to the lobby, and he would join him in 45 minutes.” Sure enough, Owen came down and asked what he wanted. Larry informed him that he was the concert promoter in Tulsa and that he believed they could make substantial ticket sales with Merle. After an hour of discussion, Owen agreed.

“I went up to the check-in desk and asked for two pieces of King of the Road Hotel stationary. We wrote up the deal, I signed it, and Fuzzy signed it. It was a big win! I flew home as soon as I found a cab.” Upon his arrival back home, he went to the then “powerhouse” country music radio station in Tulsa, KVOO. He needed them on his side and told the manager who he had booked. That experience would be his first lesson that the music business is not always a nice place.

“I knock on the door, and a man named Fuzzy Owen answers.”

– Larry Shaeffer

Music Business 101

“The manager at KVOO goes ballistic! Because all of a sudden, this nobody, me, had the Merle Haggard show. There is some hostility that comes out of that. He actually calls Fuzzy Owen and Tex Whitson and tells them that KVOO needs to bring this show and not some nobody.” Owen tells the manager that the station isn’t getting the show. He then informs him that Larry is the one who took the initiative to fly out to Nashville and ask for the show and therefore deserves the show. This gives Larry much-needed clout with the station. He then decided to bring KVOO in as a media sponsor. Now he has the performance and free publicity to promote it!

Larry booked the show in the Fairgrounds Pavilion, which held 8,000 seats. He promoted the concert with all the tenacity he is known for, including convincing Haggard to call in and do radio interviews. He actually oversold the show putting the largest crowd that has ever been put into the Pavilion. Larry walks away from the show with $40,000 in 1972. In today’s market, that equals right under $240,000!

“I was cocky! I Had two sellouts for my first two shows. The worst thing that can happen to a promoter is to make money on the first show. It’s better that he loses his ass so he can go to selling life insurance or parking cars,” Larry quips with a hearty laugh. His sarcasm is not without merit, as you will soon discover.

“The next thing I did was go out and lose all that money on more shows…as quickly as I could,” he quipped. On a roll, or so he thought, he placed his money on Country music singer Mel Tillis in Kansas.

“I had borrowed my mom and dad’s Lincoln Continental to drive up there, and I drove home sad. I had lost it all. I still hate Kansas because of those Mel Tillis shows,” he said in a comical tone. So now, he began to regroup, and a national crisis would help him do it. At his time, his partner Dave Miller decides he is out. Miller felt it was a good time to get out before suffering another loss. Larry, however, felt it was time to delve in even deeper. But first, he would need to regroup.

Little Wing Begins To Soar

In 1972 what would become known as the gas crunch hit the US, and gas prices doubled. People began immediately selling off their big cars with big block engines and looking to buy Volkswagens to save on fuel costs. Broke now, Larry saw this as an opportunity to make some cash that would allow him to book more shows and get back into the game. Once again, he borrowed $3,000 from the bank and bought cheap Volkswagens, fixing them up and selling them. This and a few other small ventures, such as selling fireworks, allowed him to continue following his dream.

These ventures kept him afloat and gave him enough money to begin making offers again to agents. He had two successful shows to give him credibility, and by 1974 things had started to move for him. He was able to bring several shows throughout the course of the year and built Little Wing into a reputable business that could deliver the goods to music fans.

Stepping into 1975, things continued gaining momentum. A phone call from Bill Elson, the man who had sold him his first show with Black Oak Arkansas, would become a call that would solidify Little Wing and propel Larry into Oklahoma’s promoter. Elson provided him with a tip and told him to book a large venue for June of 1976. He explained to Larry that although he may not understand what was happening, he needed to trust him. The biggest thing is music was coming, and he wanted Larry to be in on it.

Larry took the advice, and “Show Me The Way,” as it were, would be the way into a new endeavor for him. In January of 1976, what would become the largest-selling album of that year, with over eight million sales, was released. Pete Frampton’s album Frampton Comes Alive would go to number one and become the album of the year. The Frampton show sold over 30,000 tickets. But more than that, it was a ticket into the past that would become Larry’s future.

Swingin’ Into Cain’s

That past would be an old building that opened its ‘swinging’ doors in 1924; a place of history and ghosts of the past who spoke to Larry as though inviting him to come and take part in making history. With his profits from the Frampton show, he purchased the decaying property from its owner Marie Meyers. He owned a piece of history where Bob Wills and many other great performers had entertained crowds of Oklahomans… he owned the Carnegie Hall of Western Swing. But now that he had the ‘House That Bob Built’ as it is often dubbed, what would he do with it? That location had become part of Tulsa that people were moving away from. Larry said that even the city wouldn’t come down to sweep the streets or change street lights. Perhaps, those ghosts from the past, such as Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys, Ernest Tubb, Hank Williams, Johnnie Lee Wills, Tex Ritter, and Tennessee Ernie Ford, were asking him to save their Tulsa spiritual presence from being lost. He obliged.

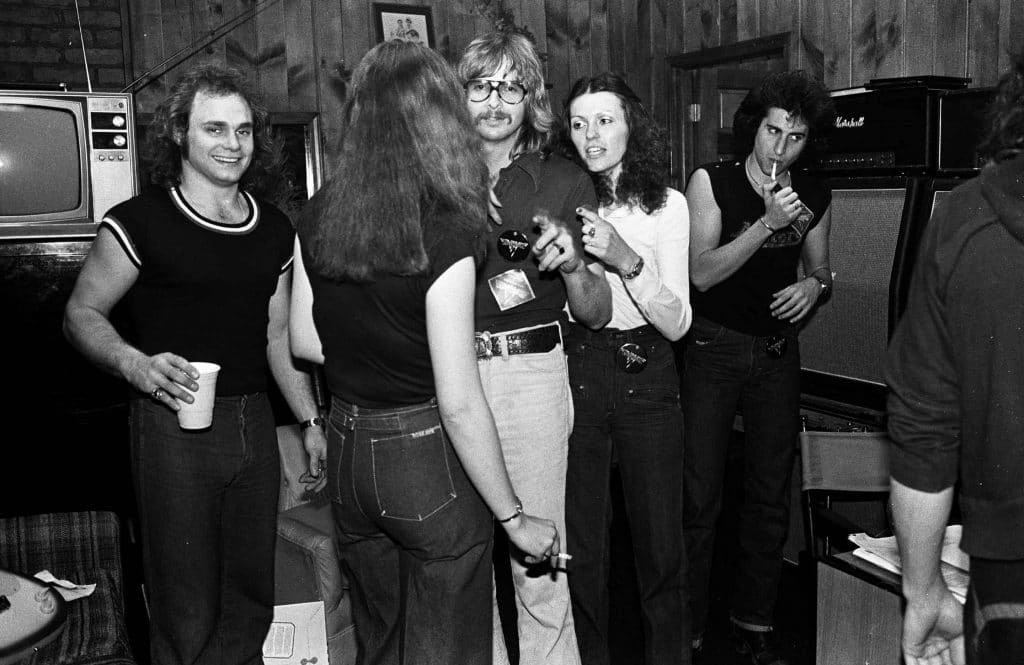

Cain’s became Little Wing headquarters and a springboard for ideas as to how he could make the ballroom profitable. Again Larry reiterated that he had no one to show him how. And yet again, Larry saw another opportunity. He began booking anything and everything he could get to play Cain’s. The opportunity arose a short time later when record companies, then in a signing frenzy for new artists, needed venues for these artists to perform. These new musicians weren’t popular enough to sell large venues but would fit nicely into Cain’s. Larry had been in a good rotation for a while and was on agents’ radars. This coupled with Tulsa geographically in the middle of the US, placed Larry on the front row of the “success show.”

It was the late 70s and early 80s by this time, and Larry was packing the ballroom with acts that were not popular yet but did have followings and were on their way to the top. Some of those acts include Hank Williams Jr., Pure Prairie League, Van Halen, Mountain, The Pretenders, Bon Jovi, Annie Lennox, The Police, and U2. Agents fed Larry these “baby bands” to help showcase them to the public. It kept the music going and the money flowing. It also created loyalty between him and the bands. This meant they were his in Oklahoma, no matter how successful they became. He was still doing arena shows in Tulsa and Oklahoma City for the more famous musicians.

One of those Cain’s shows would spark a 12-year friendship and opportunity that would grow into a very lucrative relationship for Larry. In 1978, he brought in Hank Williams Jr. At this time, Williams was still in his father’s shadow and desperately wanted to find his voice. The atmosphere of country kids at heart with rock n’ roll in their souls partying at Cain’s would be the revelation he needed to find his voice. In 1981, Larry got a call from Hank Jr.’s agent telling him that Hank Jr. would be the next big thing in music.

The agent then told him that Hank Jr. wanted him to promote his shows all across the US. Still involved with Cain’s and somewhat struggling with that endeavor, he didn’t have the money to fund Hank Jr. all the deposit money needed for a full tour. But Hank Jr. wanted him to accept Larry’s counter-proposal to promote weekend shows badly enough. He profited $90,000 the first weekend and knew that Hank was definitely the next biggest thing in country music.

Still young at this time and approaching millionaire status, he knew Hank Jr.’s shows were a ride he just couldn’t get off. His success was growing, and other entertainers such as George Strait and Reba McEntire began approaching him to promote them. Not to mention that he was still bringing big shows to Oklahoma. By 1990, now perched high upon the money tree and having a one-year-old son, he felt it was time to exit the Hank Jr. gravy train and return home to Tulsa. Hank d d not take it well, Larry said. Financially, he admits that it was stupid to end that relationship. But he had enough and decided it was time to go back home and make a lot less money but a lot more history in Oklahoma.

Please check out

Larry Shaeffer’s Legacy Part 3: On A Collision Course

0 Comments